by Rachel

1st February, 2022

On a dark, still morning in the middle of January, when most are asleep, the bottom of my garden feels like a grainy grey photo. Animation is provided by sound alone, from the river, bubbling away a short distance beyond the hedge and a robin, warming up to its morning broadcast, a few gardens down. Winter is punctuated by dramatic events – the fierce storm winds that have cleared out hundreds of dead branches, now strewn over the paths, and felled several large boughs from the crack-willows that grow along the nearby riverbank – the longed-for snowfall that lifts the light level and the mood (in our house at least) for a few days – or the unease of occasional flood water, reshaping and recolouring familiar views. But for the most part the scene is unchanged, for weeks at time. Standing in the darkness, I feel calm, almost breathless. Contrast this with a mid-summer night, with its hum, rustle, creak and whisper, when the garden seems too busy even to get dark, and by day the growth and motion is relentless in an ever-churning scene of plants emerging and fading, and insects and birds creating audio-visual white noise.

To me, change seems an intrinsic part of rewilding, but how does that work in a garden? Seasonal changes are part of any gardener’s expectation – planned for and taken advantage of. But garden rewilding perhaps means accepting of more unpredictability – how do we know when we have succeeded? Is it a continual transition, or simply a return of more native species?

The bottom of the garden, mostly hidden from the view of the house, is where the wilder changes are allowed to take place. It has had our will exerted over it in a number of ways over the years – a vegetable patch, kids play area (including the site of an enthusiastic “tunnel to Australia” attempt), badminton/football/swingball pitch, camping spot, bonfire zone, and now finally an experiment in holding-your-nerve.

I suspect the likelihood of its native state returning may be some time coming – during the veg patch years, there were several loads of horse manure laboriously dug in. Then the camping/sports arena phase demanded a dense, hard-wearing short sward courtesy of several packets of rye-grass lawn mix; whilst bonfires and hole-digging created a sticky mudflat. I’ve chucked numerous wildflower seed packs at the less trampled areas, with pitiful results. There are probably still some potatoes down there too.

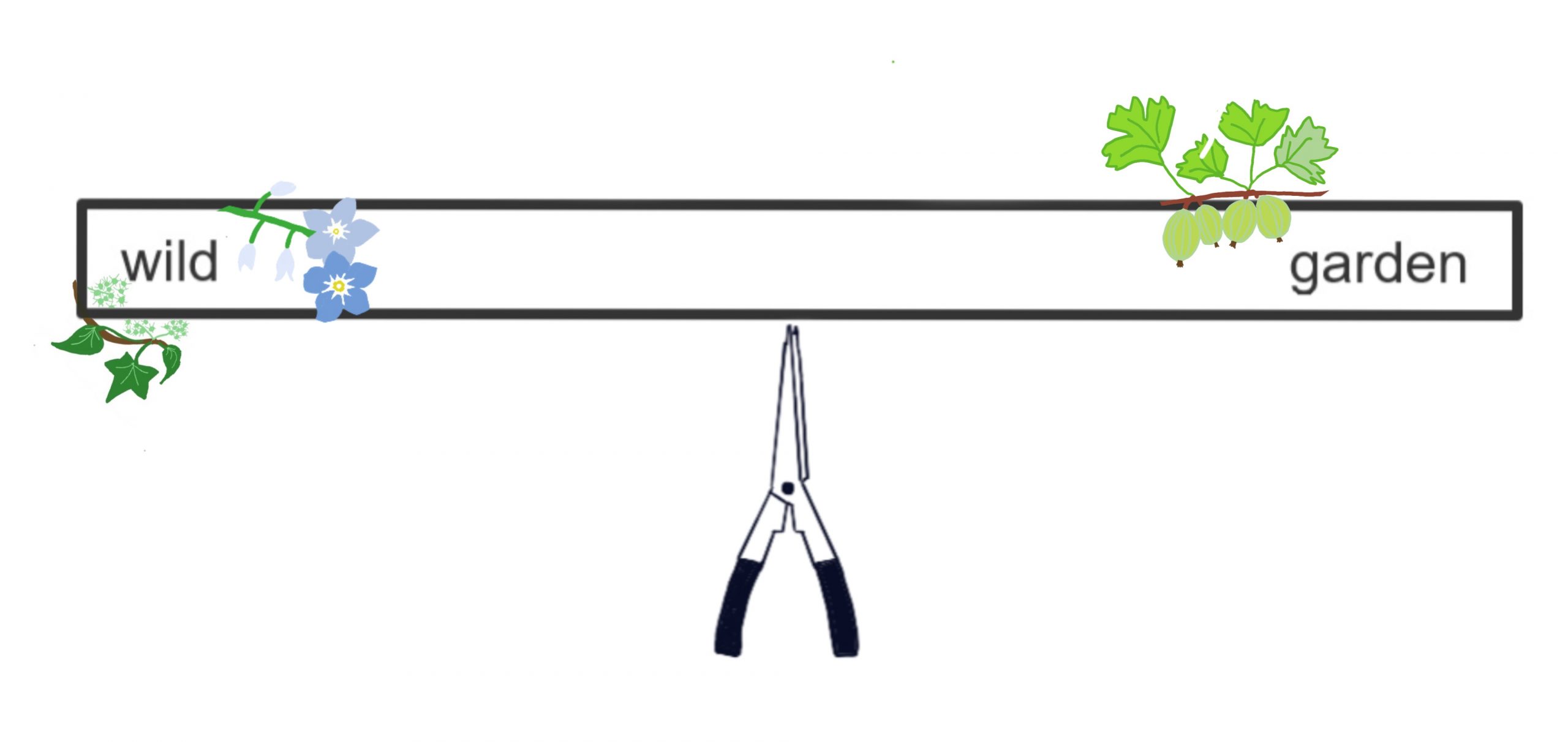

In a couple of intervening years of abandonment, there were signs of the garden’s true nature coming through – or maybe a furious response to the excesses heaped upon it – with outbreaks of nettle, cleavers and bramble, a most vicious combination to blunder into. The more gradual return of ivy, lesser celandine, enchanter’s nightshade and barren strawberry suggest that the garden would be happiest in a damp, semi-wooded state.

The grass got mowed just once last summer, and creeping buttercup then took over a large area. Curiously, the tawny owls we usually hear calling in the sycamores surrounding the bottom garden, have been absent in recent months. So I wonder whether there is a connection between food and shelter availability for field voles from the long grass, now replaced by buttercup and the absence of owls? Maybe the grass will be encouraged again. I would be sad if the owls didn’t return – I like our game of hide-and-hoot: when the owls are calling to one another, I sneak down to try to spy them silhouetted in the dusk sky, but invariably they stop calling when they hear me approach. So then I have to sit hidden for a length of time, with that dilemma of ‘the longer I wait, the better my chances’ versus ‘what if they’ve already flown away?’

In the autumn the whole patch was covered in a thick layer of leaves from the surrounding sycamores and a nearby oak, and after a month, a family member with a burst of energy raked these up – but a little late as this just left scoured mud. I’m tempted to redistribute the leaves across the area (the energetic response didn’t extend to packing the leaves for mulch as was apparently intended), but as with so much, indecision means they are still in

a pile in the middle of the mud, at least providing invertebrates with some shelter.

Blackthorn runners from the hedge are going to be removed once the leaves emerge, I don’t think we can have scrub in the space; but I wait with interest to see what mass of vegetation the spring will throw out, and then whether I’m going to want to ‘garden’ – for now though, just enjoy the quiet.