by Debbie Davitt

22nd October, 2023

I’m in love. *Sigh*… It could, of course, be just a holiday romance… after all, we met only recently whilst I was visiting the Highlands of Scotland. But, somehow, I think this love might last because the more I find out, the more enamoured I become!

The object of my affection? A tree. Or, more precisely, a species of tree: the European Aspen. Populus tremula or quaking aspen and the name gives away one of its most attractive features.

I’ve read about Aspen but I finally got up close and personal at the Dundreggan Tree Nursery at the Trees For Life Rewilding Centre at Glenmoriston in the West Highlands and after that introduction I began to spot them dotted around the landscape. Now Yorkshire folk will probably not be familiar with this tree but, like any star struck lover, I’m keen to share my newfound joy with you.

At this point, you may want to pause your reading to watch a short video showing aspen doing their quaking thing on the Mar Lodge Estate, Braemar:

I’m told the aspen should be much more widespread across the UK, but it only occurs in very limited pockets. Although native, its stronghold is the northwest of Scotland. However, I see no reason why this tree might not extend its reach down to Yorkshire – with a little help.

Firstly, a few facts for you:

- One of the largest trees in the world is an aspen tree. In Fishlake National Forest in Utah you can find one single organism which has over 40,000 trunks, covers 108 acres (43.6 ha) and is estimated to weigh collectively 6,000 tonnes. Phew!

- Populus tremula is native to Europe and Asia where it is widespread in cool, temperate regions.

- It is a fast growing and very hardy species and tolerates long, cold winters and short summers.

- The bark is silver grey which darkens and fissures with age.

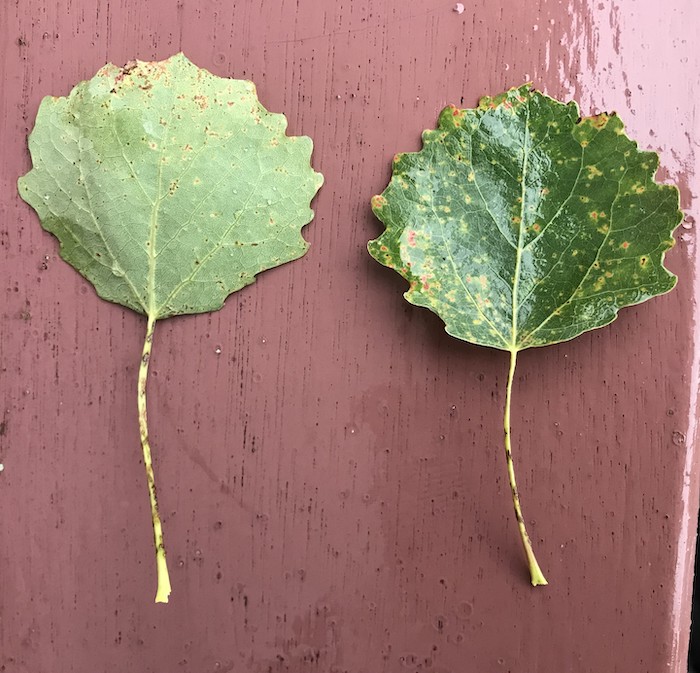

- The leaves on adult plants are heart shaped with a coarsely toothed edge. They are green, turning yellow, and sometimes red, in the autumn before falling.

- The point where the leaf attaches to the stem (the petiole) is flattened which enables them to flick and twist – which is where the Latin name comes from as the leaves tremble in the slightest wind (in the breeze of a Scottish afternoon the trees look really beautiful especially when the sunlight hits them).

- It is wind pollinated with catkins appearing in early spring on both male and female trees.

- Like other aspens, it spreads extensively by suckers (root sprouts), which may be produced up to 40 m from the parent tree, forming extensive clonal colonies.

However, it’s not the facts and figures that drew me in as much as finding out how this tree belongs in our landscape. Aspen is regarded as a keystone species because of its important ecological relationship with other species. Here’s where rewilding comes in.

It turns out aspen are also tasty to eat, maybe not to humans but certainly to beavers. Unfortunately for the tree, it is also readily eaten by deer. This means that in Scotland where there is a problem with a high density of deer they have been grazed almost to oblivion. A recent holiday to Scotland was to visit places where rewilding was happening, particularly through natural regeneration, and in those places where deer numbers are kept to a much lower level you can see the aspen is beginning to spread – but only very locally.

At the Dundreggan Tree Nursery they are keen to propagate this tree and encourage its distribution further, and quite right too, because it is special. Dundreggan is a really amazing place and well worth a visit, the nursery is a centre of excellence for propagating rare and hard to grow native species and produces around 90,000 trees every year for nature recovery projects across the Highlands and the UK. They also specialise in growing and propagating aspen and it was fascinating to find out how they do this.

Aspen needs some help. It’s believed that most of the trees left in the wild are male and because it’s a dioecious species both male and female plants are required in order for viable seed to be produced. However, if you’ve got mostly male, you’re not going to get much seed. What they’ve been doing at the tree nursery is trialling different ways of getting the pot grown stock plants stressed enough to produce seed. A natural reaction with a lot of plants when they experience physical stress e.g. a drought situation or an attack from grazers is for them to put all their energy into producing seed to secure the future of the next generation (it’s the same reaction that is prompted when you dead head a plant to produce a second flush of flowers).

In poly tunnel number 6 where the stock aspen trees are growing we were shown how they are ring barking the trees, removing a strip of bark part way up the stem and then re-attaching it. Other trees are deliberately underwatered to mimic drought. The tree usually survives but the stress is enough to prompt it to produce seed which is then collected and propagated. All good but pretty labour intensive.

On the right hand photo above see how the leaves above the ring barking are already changing colour – an indication of plant stress.

Back to the beavers. I find that research has shown that ‘aspen and beavers have a special connection as aspen are the preferred food and building material of beavers. Specifically, beaver fell mature aspen using the large limbs and trunks for dam and lodge building, while caching smaller branches to eat during winter. Beaver are known to travel further from stream channels to harvest aspen trees than other woody species’ (Ref 1). Whilst this study refers to the United States the same seems to be true of Eurasian beavers and the native aspen.

Now, because aspen are so popular with beavers, in some Scottish quarters there has been a nervousness about reintroducing beavers to areas where pockets of aspen cling on for fear that they might destroy all the trees. However, if people are stressing trees artificially to make them produce seed, perhaps, just perhaps, in a natural situation it would be the beaver that would be doing this. After all, beavers and aspen trees have co-evolved and it doesn’t make sense for the beaver to wipe out its favourite food. So here’s a neat thing: it seems very likely, when you stop and think about it, that when a beaver stresses an aspen by gnawing at it that would be the trigger for the tree to send further suckers up and create seed. So actually, perhaps all this time what’s really missing is an ecological relationship which we have forgotten about because we haven’t seen it for 400 years. Bringing back whole ecological systems is what rewilding is all about and I just find that so exciting.

Credit: Debbie Davitt

My conclusion is that regardless of whether or not we have beavers living wild in Yorkshire any time soon I think we should be preparing the way and planting aspen. It’s not a tree for your garden because it grows to 25m and, as previously mentioned, spreads by suckers. However, if you have the right conditions – an open, sunny position and moist soil – then this is definitely one species I would consider planting on your land. If we plant the trees now, then when the beavers arrive they will be very happy beavers!

Links and further information:

Evidence that beaver reintroduction will not harm aspen: Jones, Kevin & Gilvear, David & Willby, Nigel & Gaywood, Martin. (2009). Willow (Salix spp.) and aspen (Populus tremula) regrowth after felling by the Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber): Implications for riparian woodland conservation in Scotland. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 19. 75 – 87. 10.1002/aqc.981.

Trees for Life Dundreggan tree nursery

Mossy Earth: Restoring Aspen – Returning a Keystone Tree to the Scottish Highlands