by John Hartshorn, Yorkshire Rewilding Network Trustee

20th April, 2021

How old are you?

It’s not meant to be a rude question. But your age will determine what you consider to be ‘normal’ when it comes to nature’s abundance and species richness in the UK.

If you’ve read the State of Nature Report 2019 then you’ll know that one of its key messages is that the abundance and distribution of the species across the UK has, on average, declined since 1970. I won’t quote specific examples here because it’s too depressing and you can read the report yourself, but you’ll likely be very familiar with the regular news stories of nature’s continued decline with each passing year. And, actually, even before 1970 nature had been massively depleted by centuries of habitat loss and degradation, pollution, and persecution. It’s not just here in the UK, of course – the 2020 global Living Planet Index reported an average 68% fall in monitored populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish globally between 1970 and 2016.

When changes happen gradually over a long period of time, we often fail to notice them. We might remember and reminisce about nature’s abundance in the days of our youth. Or perhaps we are younger and don’t have such memories and likely have little or no knowledge of what nature was like in days gone by. Whatever our age, we often subconsciously accept that how things were – how nature was back then – has changed. With each passing generation we unwittingly accept less and less as the ‘normal’ abundance and distribution of species. And what’s worse, we fall into the trap of basing our aspirations for nature’s recovery on what was ‘normal’ in our youth or perhaps what was ‘normal’ for our parents – just a single generation back.

What’s happening over the long term is that each successive generation sees a ‘normal’ that is made up of less abundance and less diversity. In other words, the ‘baseline’ against which we measure and compare what is ‘normal’ is gradually, often imperceptibly, shifting. Those who first saw an ecosystem in 1970 will likely have a very different idea of what is ‘normal’ than those who have only experienced it in the past couple of years. These different perceptions of ‘normal’ are known as “shifting baseline syndrome” – a gradual change in the accepted ‘normal’ for the condition of the natural environment that comes from a lack of experience, a lack of memory, or a lack of knowledge of its past condition. Each new generation becomes normalised to an impoverished version of the environment and cannot appreciate what is missing, what has already been lost. Over successive generations, ‘normal’ gets passed down and amplified because each generation’s starting reference point for ‘normal’ is inherited from the previous generation’s ending point for ‘normal’, which in turn was inherited from the previous generation’s ending point for ‘normal’. A progressive decline in nature’s abundance and diversity is being passed down the line, stretching back for many generations.

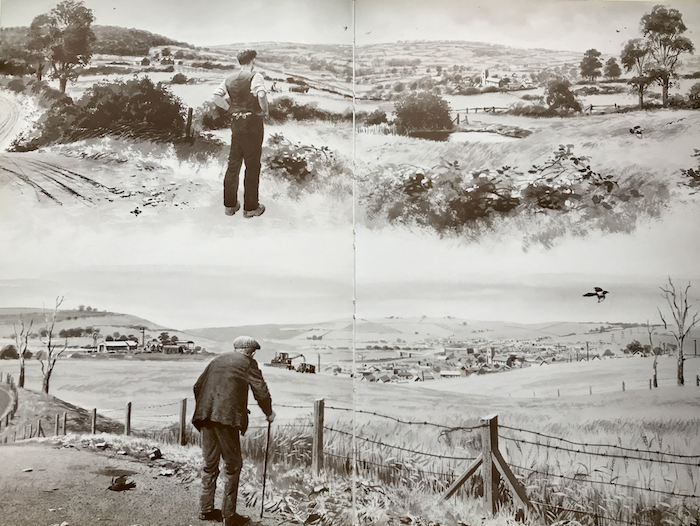

I think these sketches by Rodger McPhail from 1986 sum this up rather well, if leaving me with a deep feeling of desolation. I wonder what the old man would be looking out across now, in 2021?

So, should we abandon all hope and accept that nature will inevitably continue to spiral down? Not at all. In having observed and acknowledged declines in nature and having rather grandly named our changing expectations of what’s ‘normal’ as “Shifting Baseline Syndrome”, we’ve at least acknowledged that something has been going wrong. And that means we can do something about it. We have a new approach to add to the existing portfolio of conservation measures. In fact, it’s so new it’s only millions of years old. What? Yep – it’s “rewilding” and the clue is in the “re” bit. It’s all about allowing ecological processes and functions – that have been evolving since the appearance of the first micro-organisms – greater freedom to recover. We know that nature often bounces back spectacularly well and pretty quickly if allowed to do so, albeit sometimes with a bit of help from us to get the party going again. With the main goal of rewilding being to restore lost ecosystem processes and functions, rewilding approaches – whatever the scale and level of initial intervention – allow biodiversity and abundance to recover, possibly along different trajectories to those of the past. In fact, that’s the most exciting part of the approach – it lets nature decide what the future looks like.

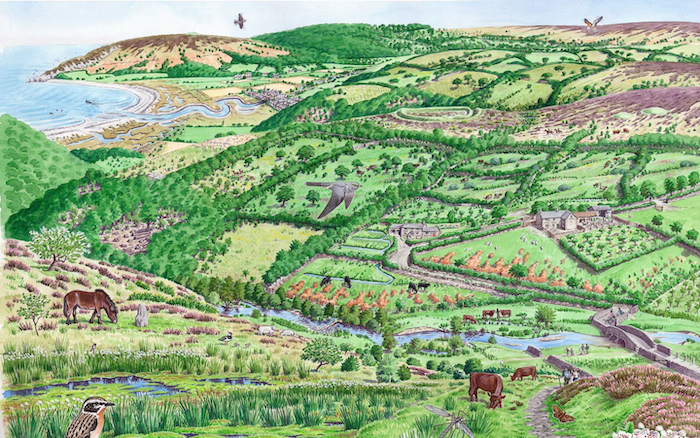

Perhaps a future more like this…