by Sarah Mason

8th March 2025

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer is one of my favourite books. It explores the deep connection between humans and the land, emphasising the reciprocal relationship we share with nature. Although most of us in Yorkshire aren’t currently living in a gift economy of reciprocity, we can learn many lessons from the Indigenous worldview. The idea that “what is good for the land is good for the people” resonates deeply with me, highlighting the importance of making good decisions on how we manage our land, whether it’s our gardens, city centres, farms or national parks.

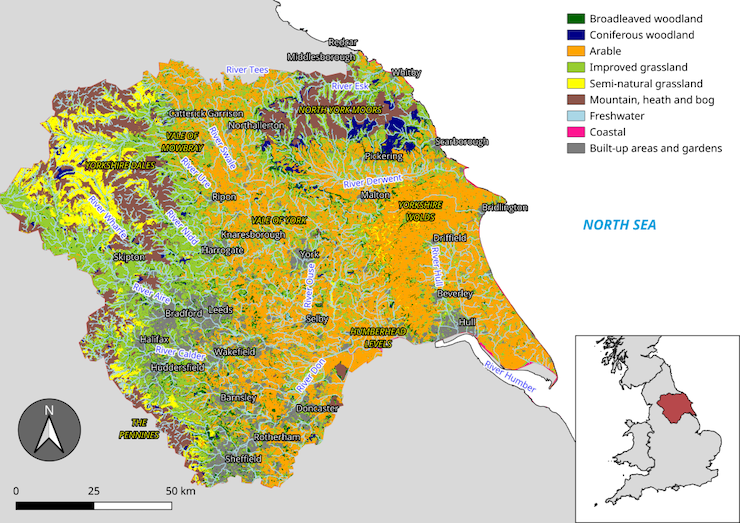

There are more than 5 million of us that live in Yorkshire, alongside another 40,000 other species [i], and we all interact with the land in some way. Yorkshire is also home to three National Parks, two National Landscapes, the most northerly chalk streams in the world, globally significant peat bogs, and some of England’s most fertile land. We’re known for our high-quality wheat, barley, oats and corn, and we’re nationally significant when it comes to food security.

But land is a limited resource. A limited resource with increasing demands for food, water, nature, housing and energy. It’s crucial we manage it sustainably to ensure it continues to provide life, food and meaning for future generations. A report by the Royal Society in 2023 [ii] reviewed all the current policy demands on land, and concluded that by 2030 we need an additional 4.4 million hectares of land (18% of the total country) to deliver all our net-zero, biodiversity and development objectives, assuming levels of agricultural production remain similar.

When it comes to making space for nature, the government has committed to protecting 30% of land and sea for nature by 2030 (‘30 by 30’), and the Yorkshire Rewilding Network advocates for this 30% to be rewilded [iii]. However, nature is competing with a vast range of demands, including targets to scale up bioenergy crop production, solar farms, building 1.5 million new homes, and providing a growing population with food and water security. As our climate changes, we also need to be adaptable and consider where things like our future floodplains and coastlines might be.

Source: Royal Society Report on Multifunctional landscapes (2023)

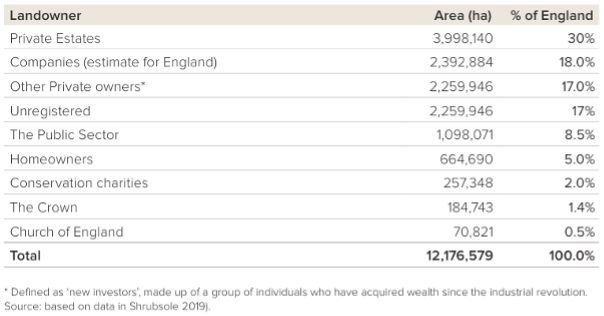

Considering these demands alongside our current land ownership model, and with nature markets still immature, it may seem like an impossible dream that rewilding will be able to compete with these wider economic and social demands. Making space for nature still primarily relies on private altruism and charitable organisations. The rewilding approach needs whole landscapes to be given space for nature. In the words of Sir John Lawton, we need bigger, better and more joined up.

This is why rewilding needs a land use framework – a framework that recognises that nature underpins our economy, health and wellbeing. A land use framework needs to set out principles to guide decision-makers to minimise trade-offs and unlock sustainable, holistic approaches to land use. DEFRA has been working on such a framework for several years and plans to publish the final version later this year.

There are solutions and ways to navigate these competing demands. While we might not be able to create more land, we can find ways to use our land more effectively and make better decisions. For example, let’s not rewild or build solar farms on prime arable land, or build key national infrastructure on land at risk from sea-level rise. Instead, let’s look at how different land uses can coexist, and start to think about our land as multifunctional. For example, floodplains store water and they are also nature-rich habitats, urban development can be interwoven with nature corridors, solar panels can be installed on rooftops, and highly productive arable land can be farmed regeneratively.

Rewilding sites are some of the best examples of multifunctional land use. In Yorkshire, for example, Denton Reserve in Wharfedale is a 2,500-acre estate that is combining landscape-scale nature restoration of national significance with regenerative food production. Likewise, Kingsdale Head occupies 1,503 acres of upland in the Yorkshire Dales and is rewilding at landscape scale while also producing high-quality beef from its herd of wild-living Riggit Galloway cattle.

When it comes to land use, it’s not about binary choices; we can deliver more with the land we have if we think about which land uses can work together.

As well as thinking about multifunctional land use, another opportunity is to think creatively about how we can reduce the demands on our land. Seventy-two percent of England’s land is currently used for agriculture. Where are the opportunities to free up some of this land while maintaining food security and protecting our most productive land?

The National Food Strategy (2021) [vi] estimated that 5–8% of English land needs to be released from agriculture by 2035 to meet climate and nature targets (the ‘30 by 30’ ambition again). It also points out that this is entirely possible given that the least productive 20% of farmland produces only 3% of our domestic calories. It goes on to say that this level of production loss could easily be offset by small dietary changes in either total calorie consumption or levels of consumption of meat and dairy.

Do we even need land to produce our food? Well, the short answer is yes, but can we reduce the demand on our land by innovative food-growing? FixOurFood is a multidisciplinary research programme based at the University of York, aiming to transform Yorkshire’s food system to one that is regenerative. One of their projects is Grow It York, an indoor community farm supplying food hyper-locally, all year round. Similarly, at the end of 2024, Leeds University opened its new £38 million centre dedicated to mainstreaming alternatives to animal-based protein. These are just two examples of where Yorkshire is leading the way in innovative approaches to reduce the ever-increasing demands on our land.

For a land use framework to deliver what we need, we require joined-up strategic thinking. Communities need to be at the heart of decision-making, and funding needs to be meaningful and well-designed. Multifunctional land use needs to be a core part of the framework, but more than this, it must recognise that land use is the point of intersection for social, climate, nature and economic needs. Demand on land must be considered in all policy decisions across all government departments.

We need a land use framework that’s bold, transformative, and more than just guidelines. Most importantly, we need nature to have a prominent voice.

DEFRA is currently consulting on a National Land Use Conversation in preparation for publishing a Land Use Framework for England later this year. The consultation is open until 25 April 2025. You can respond to the consultation here.

Referenced links:

[i] Yorkshire Wildlife Trust: State of Yorkshire’s Nature

[ii] The Royal Society: Multifunctional landscapes

[iii] Yorkshire Rewilding Network – Speak up for Nature!

[vi] The National Food Strategy